Love and Linguistics III

Note: This post is part of a series. You may wish to read first Love and Linguistics Part I & Part II.

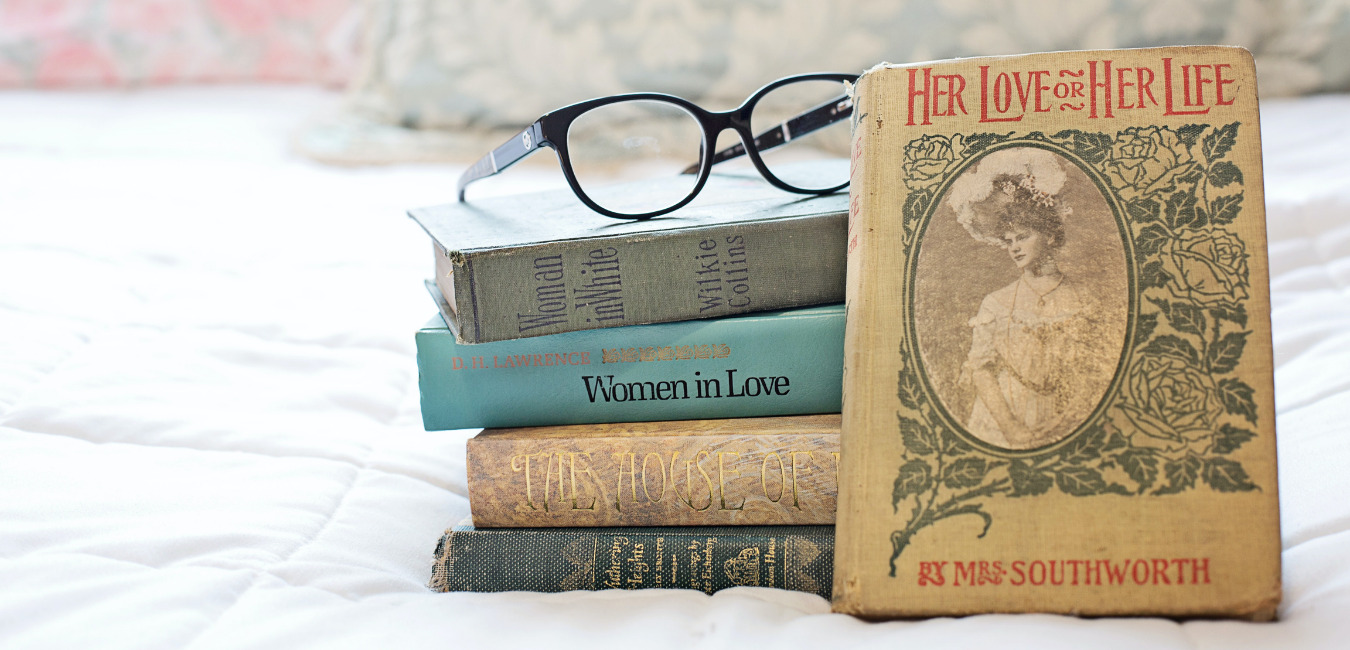

The pleasure I take in exploring the many varieties of romance has two sides: the love side and the linguistic side.

The love side. I love setting my stories in different times and places, be it in a castle in medieval England, the great outdoors of the American West, a seventeenth-century shipwreck in the Caribbean, or a motorcycle club in present-day Vietnam.

In different times and different places love relationships necessarily play out differently. The kinds of interactions my characters have in an elegant drawing room in Regency England with strict rules of decorum are radically different than the kinds they have in an edgy BDSM club where nudity is a norm and Doms with good whip hands are in demand.

The linguistic side. In order for me to convincingly portray these different times and places I have to learn new vocabularies.

In a 12th-century medieval romance male characters dress in tunics, chausses, cross-garters, and

often hawberks, which are long tunics made of mail. The women wear kirtles or bliauts and circlets in their hair or perhaps a wimple.

If the story is set in a castle, then I have to know architectural terms like keep, parapet, barbican, and portcullis.

If it’s set in a town, then my characters are sure to pass butchers swilling blood and offal (I love that word!) into the gutters. If it’s set at court, then knowledge of heraldry is necessary. The descriptions of various shield patterns are complicated enough:

There isn’t enough room here to describe the intricacies of the terminology involved in describing a coat-of-arms.

By way of contrast, in a 21st-century mixed martial arts romance my heroine will wear compression shorts and a sports bra for training and a gi for competition.

I have to know what a training gym looks like, and I have to stock it properly with speed bags, body snatcher bags, grapple dummies, punching mitts, kettlebells, and the like.

I also have to know the various MMA holds – cool words like kimura and gogoplata – and what a jailbreak is.

For my time-slip (reincarnation romances) trilogy, I used a science mystery as part of the plot in all three. The first, The Blue Hour (affiliate), involves cancer research and the enzyme telomerase was important. The second, The Crimson Hour (affiliate), was about oceanography, and red tides and algal blooms come into play. The third, The Emerald Hour (affiliate), is about the rubber trade, and the plot turns on finding a strain of rubber trees resist to certain fungi, such as macrosporum.

Learning about each of these sciences was like learning a new language.

Speaking of the time-slip series, I sometimes I have to know an actual new language in order to convincingly invoke a time or a place. I know French well. My first time slip, The Blue Hour, is set in contemporary Raleigh-Durham, Chicago, and Paris as well as Paris of the 1880s.

I didn’t put Eh, oui or Mais non! in the mouths of my French-speaking characters when they’re speaking English. That just wouldn’t happen in real life.

The trick was to decide exactly which French words would provide the hint of dill in the sauce. So I had my one of my French characters slip in the word s’encanailler ‘to slum’ at one point and another point another one used bredouille ‘empty handed.’ Out of the way words, certainly, but perfect in their contexts.

After I spent six months in a language school in Saigon, I wrote the Forest Breeze (affiliate), which is set in Vietnam. I was happy to use a somewhat familiar word to Americans, namely phở, the soup the Vietnamese eat for breakfast. By the way, it’s not pronounced fo but rather FU-uh?, where the question mark indicates the tone dấu hỏi.

I used a couple of other, well-chosen (I hope!) Vietnamese words, but not a lot. When I’m writing a story, I’m writing a story and not giving a language lesson.

Final note: I teach History of English. When we come to the Renaissance, it comes up that the vocabulary size of the works of John Milton is about 8000 words, while Shakespeare’s is more like 30,000. It’s not necessarily the case that Shakespeare knew more words than Milton, but he certainly wrote about a greater range of things, including gardening tools.

I’m not saying I’m Shakespeare. But I am saying I share his exuberance for words from all registers of English and any other language I can get my hands on.

Categorised in: Language, Love

This post was written by Julie Tetel Andresen

2 Comments